Yeast – Baker’s & Natural

By: RedmanShop | February 17, 2025

Baker’s and Natural Yeast

Baker’s and Natural are two types of yeast more commonly used in baking, each providing the basis for dough fermentation. Yeast requires special conditions for it to perform consistently throughout the fermentation process. Yeast growth is shown by its increasing capacity to multiply and bud. The conditions necessary for its growth are water, food, oxygen, time, temperature, and appropriate acidity/alkalinity level (pH).

Baker’s Yeast

Baker’s Yeast is a commercial product available in several forms, such as low-sugar or high sugar-tolerant varieties. The choice of which yeast will depend on the dough’s sugar levels. Low sugar yeast works well up to 10% sugar content, whereas high sugar yeast works best in doughs with above 10% sugar content. To check the Percentage of sugar in the recipe, use the Bakers Percentage calculation method, as explained in Part Two.

Types of Yeast

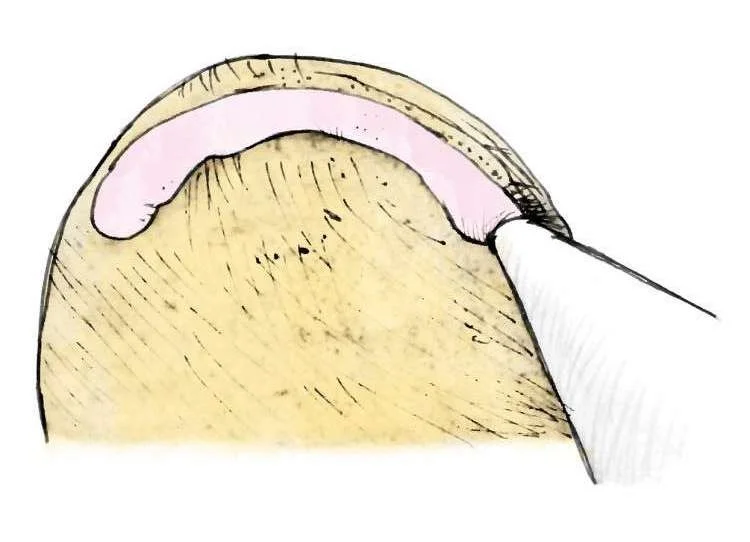

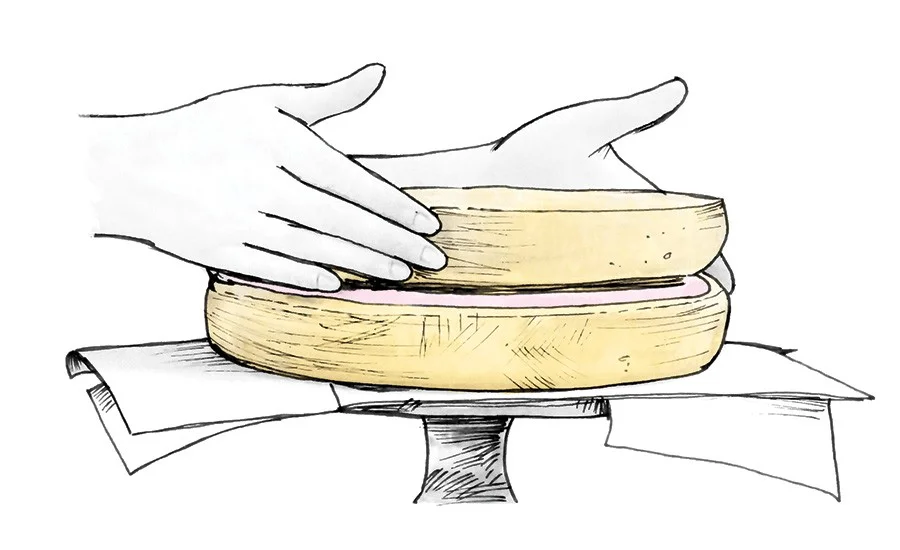

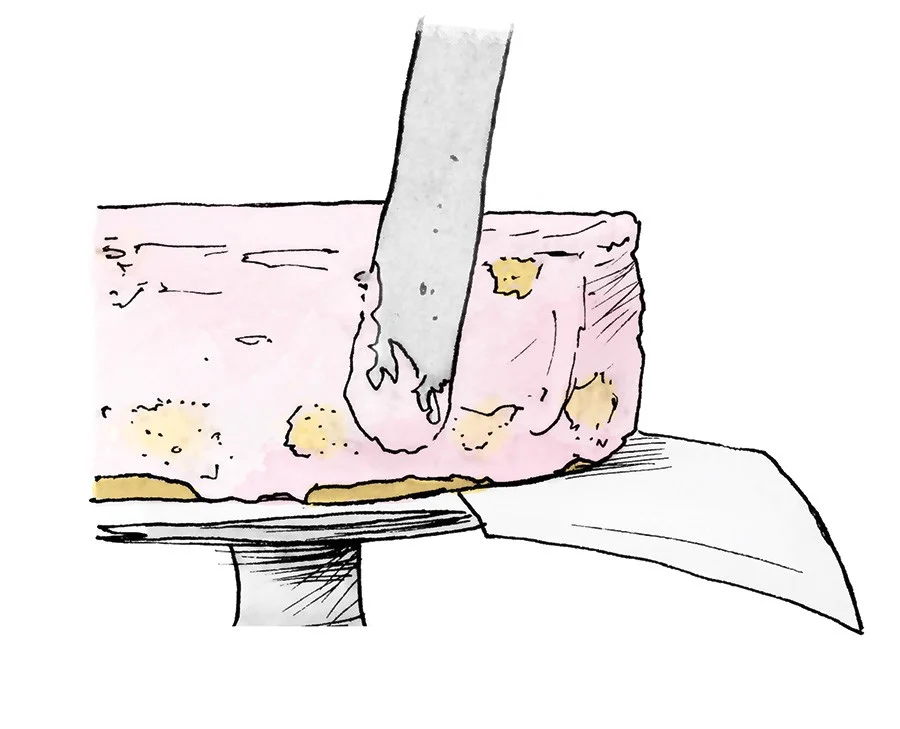

Compressed : Block form is the most common. It is also available in flakes for larger plant bakeries.

Dried Yeasts: Instant Dried / Instant Active DriedStrains of yeast that have had the water removed. The yeast is re-activated by mixing with warm water. It is added directly into the dough when it is mixed.

Note: To convert fresh yeast usage to dried yeast, multiply the quantity by 0.4.

High and Low Sugar Yeasts

The type of yeast used in the dough relates to the amount of sugar in the formula. For lean dough formulas, sugar will range from 0% – 10% on the flour weight. In rich sweet dough formulas, sugar can be 12% to 20% of the flour weight. The high sugar yeast strain is required in these doughs as regular yeast will not be able to create enough fermentation activity. The dough would move slowly as low-sugar yeast cannot cope with high-sugar levels.

Storage

For dried yeasts, refrigeration in airtight containers is most suitable. Fresh compressed yeast also needs refrigeration and is wrapped in appropriate paper to prevent it from drying out. Buy small packs until confident so as not to waste ingredients. Do not purchase large pack sizes (500g) at first, as they deteriorate with age.

Must Know

Yeast is a living organism and requires attention to detail to obtain a consistent result. Buying yeast in individual small sachets is recommended rather than a large amount. Once opened, its gassing properties deteriorate.

Natural Yeast – Levain (Sourdough)

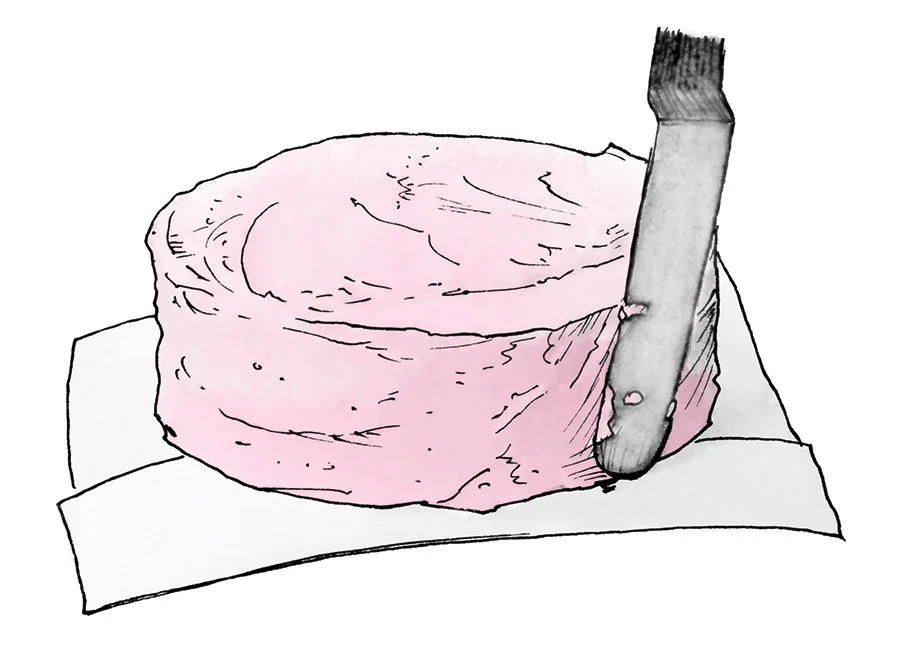

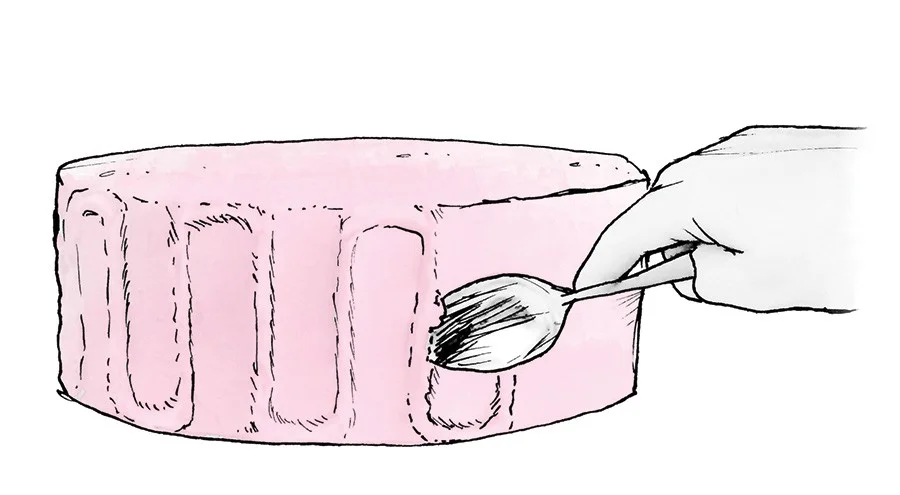

A mix of flour and water (equal parts) stands in a clean container to attract the wild yeast cells and organic bacteria in the air. Once evidence of activity (bubbles or air pockets visible), a regular feeding process using equal parts of flour and water begins. The action is repeated for the next seven days. The result is that Levain replaces baker’s yeast for dough fermentation. For further details refer to page 71, Part Three on practical baking.

Storage

It is best kept refrigerated during the building stage and upon completion of the starter. Any leftovers from daily production must be returned to the mother and kept under refrigeration.

Must Know

Building the Levain is a slow and steady process requiring care so that the foundation is solid and healthy. Once you have the Levain, you must feed it so it is ready for use before making the dough. The flour used in the starter and feeding must be unbleached, with the most suitable being a medium protein.

Fermentation

Yeasts are used as an aerator, affecting product structure, flavour, volume, and quality. The yeast’s performance depends on the amount of water, its temperature, and the finished mixing temperature. It will be challenging to control this process as it could move too quickly or slowly at times, so it is crucial to have a clear understanding for success to follow.